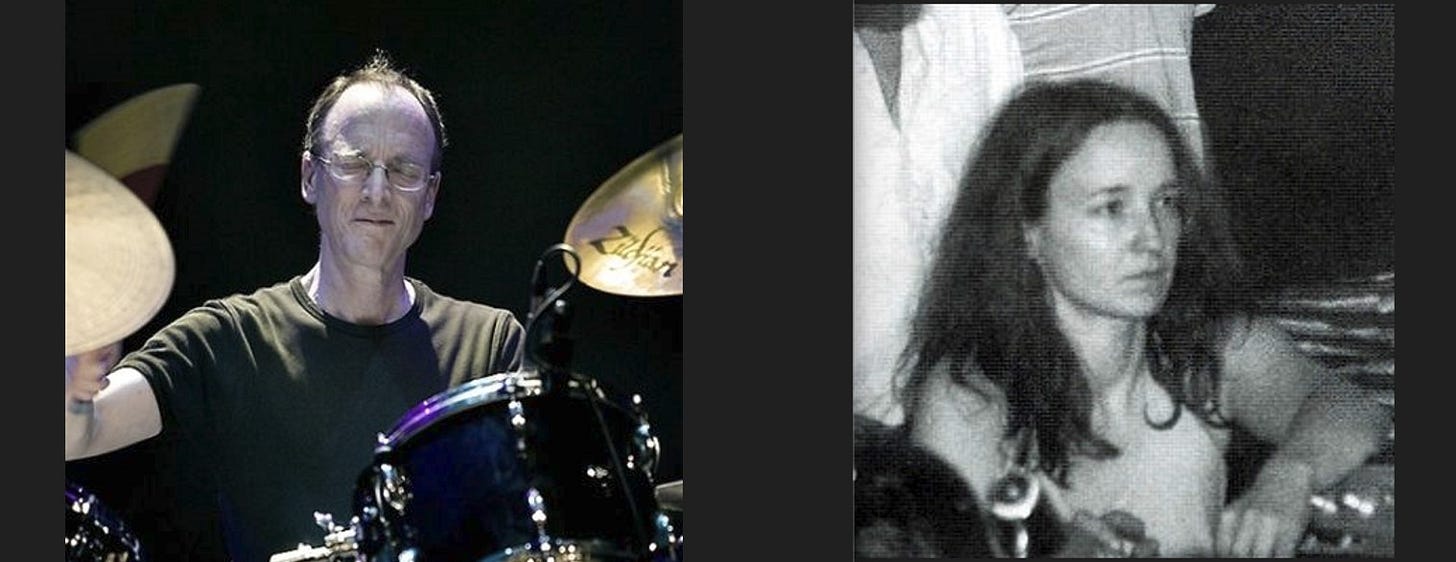

This interview has been a long time in the making, and worth every minute. After spending months trying unsuccessfully to schedule a Zoom call, we opted to do this via email. Chris also suggested I contact Maggie, and I had a separate email conversation with her. I combined the two below.

I recently started researching what we talked about so I could put it in context for you, and that’s turning into another full length article that I will post soon. For now, let me show you what was going on in Chris and Maggie’s world around the periods of time that we focus on in the interview. These are the times that they met Giorgio Gomelsky.

The first thing to know is, when Virgin Records got started in 1973, they were carving out a niche by signing avant-music bands. Here are just some of the records they released in that year:

Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield May 1973.

Flying Teapot (Radio Gnome Invisible Part 1) by Gong (produced by Gomelsky) May 1973. Note: Cover Design by Maggie Thomas and Daevid Allen.

Mekanïk Destruktïẁ Kommandöh by Magma (produced by Gomelsky; partly recorded at Virgin Records' Manor Studios but released by A&M) May 1973.

Faust IV by Faust June 73.

Legend by Henry Cow September 1973.

Marjory Razorblade by Kevin Coyne October 1973.

Angel's Egg (Radio Gnome Invisible Part 2) by Gong (produced by Gomelsky) December 1973.

There’s so much to write about in the above list alone that it will likely take up multiple chapters in my work-in-progress book The Gomelsky Recordings. For now, all you need to know is that Tubular Bells was the pivotal release at the time, although nobody would know this until the very end of 1973 when it got picked up by William Friedkin for his movie The Exorcist.

In the meantime, the camaraderie that had developed around Virgin’s residential recording studio The Manor would give Oldfield a large pool of musicians to draw on when Richard Branson insisted that he perform the piece live on BBC. There were at least two live performances done featuring most of the members of Henry Cow, along with Oldfield’s then girlfriend Maggie Thomas who was part of the “girlie choir”.

Tubular Bells in 1973 with most of Henry Cow:

https://preparedguitar.blogspot.com/2014/03/mike-oldfield-co-tubular-bells-live-set.html

This was the scene when Gomelsky showed up at The Manor with demos of Magma’s soon to be recorded and released MDK.

Fast-forward to 1978. I’m just going to show you the info from Chris Cutler’s website that summarizes what he was doing that year leading up to his involvement with Gomelsky’s Zu Manifestival in NYC.

http://ccutler.co.uk/ccabbreviated.htm

1978

January to June saw the last half year of Henry Cow in which we set up Rock In Opposition, organised a festival in London, wrote an entire set of new material, underwent several small personnel changes, revisited all the countries we'd ever played in and recorded our last LP (Western Culture). Our penultimate concert was in the cathedral square in Milan on July 25, 1978 (our last concert was to have been a festival in London, which we showed up for but as a result of eccentric planning on the promoters part, were unable to perform at). After this we all went our various ways.

This was also when I founded Recommended Records (with Nick Hobbs) - an alternative, independent, non-commercial record distribution, mailorder network and label. And the group Art Bears (with Fred Frith & Dagmar Krause).

After a month In Spain with Daevid Allen and Gong, I went with them in a cardboard airplane (featuring an exciting unexplained emergency stop in the Azores) to play at Giorgio Gomelsky's Zu Manifestival in New York, where I also played with Fred Frith and Peter Blegvad.

So there you have it. The stage is set. Let the interview begin …

[Rick] When did you first become aware of the name Giorgio Gomelsky?

[Chris] On the cover of the 5 Live Yardbirds album (I used to go to see The Yardbirds regularly back then and I bought the LP as soon as it came out). Also his name cropped up frequently in the music press.

[Rick] This was an exciting time to be a music goer in London. Can you describe what a night out was like for you at that time? What were the clubs like? There are photos of fans literally hanging from the rafters at the Crawdaddy.

[Chris] In the earlier period there weren’t so many clubs, except in London, so most of the gigs I went to - since I lived in the suburbs - were in town halls, church halls and pubs. And they were dances. My first local concert venue was Wallington Town Hall (I don’t know who the organiser was) where groups like the Yardbirds, the Downliners Sect, The Who, The Animals, The Herd, The Birds, The Zombies and the like, played, as well as lesser known R&B bands. The Yardbirds were almost regulars there. [I remember the sensation they caused when they showed up with their first 100-watt PA system, with two columns of 8” speakers; we’d never seen anything like it,] A couple of years later, the band I was then playing in was the regular support act at a church hall in Sutton, where there were weekly gigs, featuring the likes of Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Graham Bond, Rod Stewart, The Downliners again – and so on. And then there were the London clubs circa 1967: Ufo, Happening 44, the 100 club, the Marquee - and especially regular concerts at the Roundhouse in Camden. In the earlier years – in Wallington – I saw the divide begin between people who wanted to dance and people who just came to listen. The hall was a large rectangle with a stage at the front and seats along both long walls - boys on one side, girls on the other - that was the standard set-up for dances. Gradually, a growing number of people just stood at the front and watched the bands - with the dancers hopping about behind them. A lot of those standing were musicians, some who’d come to see certain players (like Paul Samwell-Smith or Pete Townsend) and others just to listen. As the months went by the ratio of dancers to watchers changed in favour of the watchers. That was also a reflection of the programming, of course, which favoured the more musically interesting bands. That said, until 1966 or so, the repertoire of nearly all bands was drawn from the same R & B, Chicago, Chuck Berry/Rock and Roll pool; there was a whole catalogue of songs everyone in a band had to know. By the time of the concerts in Sutton, more or less the whole audience was watching, with few dancers. It was the same in the London clubs, where more and more gigs had light shows and movie projections, as concerts moved toward being visual and immersive events.

[Rick] Did you ever visit any of Gomelsky’s Crawdaddy Clubs?

[Chris] No.

[Rick] Did you ever see performances by the Yardbirds or Soft Machine or any of the other bands he was working with in his London days?

[Chris] Yes, a lot of them, and often. By the time of Soft Machine I was also in a working band playing in some of those clubs. I got to know Daevid, Robert and Kevin fairly well around then (and worked with them).

[Rick] Did they mention Gomelsky?

[Chris] Not that I can remember.

[Rick] Eventually, Gomelsky would help you tour France. How did that come about and what were the discussions like with him at that time?

[Chris] The Virgin agency was doing a terrible job getting us gigs, and finally there was an opportunity to play with Robert (Wyatt) in Paris. An agent of Virgin's in Paris was asked to get some other French bookings for us at the same time. It all seemed to be going ahead and then, very shortly before we were due to leave, all the extra concerts were called off (if there actually had been any in the first place). For many reasons we were desperate by this time to get into Europe, so we tried to find another route. Maggie Thomas and I were deputized to go to Paris and see Virgin’s agent and try to salvage something from the wreckage. He told us there was nothing he could do. Maggie, who knew Giorgio quite well from The Manor, suggested, since we were in Paris, we go and see him. She had his phone number and called him and he invited us round. Chez Giorgio, wine appeared and we sat and explained our situation. Initially Giorgio said he didn't think he could help us…. it was such short notice... he had his hands full... but we continued to talk - and drink. The talk became general: music, philosophy ('Man and God and Law', as Dylan says). After a couple of hours, in the middle of whatever point we'd reached, Giorgio suddenly picked up the phone and said - I paraphrase - “Georges I have some people here I think we should help, can you come round?” Georges came and he and Giorgio discussed what could be done at short notice - what Magma gigs we could be slid into…. what else? Essentially, Georges was put on our case and we worked with him and (later) Christine for years thereafter, mostly on the MJC circuit Giorgio had established for Magma, as well as the occasional festival.

[Maggie] MJC (Maison des Jeunes et de la Culture), a building rather like a Salle de Fêtes in every village, were in every large town and regional capital. They used to receive government money to put on concerts and events, quite a bit it seems, because they could pay a decent sum to large touring groups plus accommodation and dinner.

[Chris] Georges Leton ran a booking and management agency and was essentially Magma's manager (and Jochk'o Seffer's and probably other bands too) and organized concerts for them all – and then for us. Christine Gomes joined the agency a little later and became his business partner. They looked after us, came to the gigs, sorted out our problems. They were efficient, nice people - ask Maggie, she knew Christine quite well.

[Maggie] I met Giorgio at the Manor in spring 1973, not sure when exactly. He came to the Manor with a demo of Magma’s Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh, which he played for everyone in the control room at the studio. It was absolutely hair-raising, fantastic and - as I thought at the time - evil!!

He stayed a few days and we got to chatting. I had no idea who he was, but he was certainly colorful and interesting. There was a platonic relationship which I think Giorgio really liked, someone he could talk to about everything, he was a bit of a sexist but that went with his forthright character. And was pretty normal at that time.

The next thing I remember was arranging to meet him at the Roundhouse for a Magma gig, I suppose it must have been before the recording of the backing tracks at the Manor, since I didn't know any of the group; but I did get introduced to Georges Leton (who spoke no English at that time, I'm pretty sure) and we had an instant liking for one another.

Then I think Giorgio was at the Manor for the recording of bass, drums and piano backing tracks of Mekanik. That was with Jannik. I may have been the best French speaker at the Manor at that time, although I'm sure Simon Heyward could do so as well, so I got to know Christian a bit. Very magnetic and charming. Giorgio swanned in and out, no other way to describe it! He would dominate any room he came into. So it must have been then that we got to know each other and chatted about everything except music (particularly cooking!). He did tell me that he found Keith Emerson playing in a pub somewhere, I didn't see a reference to that in the Giorgio book. [Note: find out more about this Keith Emerson story here … https://rickrees.substack.com/p/whats-happening-at-the-non-writer]

He then went to live in Paris and promote Magma. I don't know if I came across him in France in 1973 at a Gong gig. The two groups were touring constantly in France, doing the MJC.

So when I joined HC, there was a supposed Virgin touring agency and their French representative was a guy called Assad who lived in Paris. We had the Robert/HC gig at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées around May 6th 1975 and we went to Assad to ask him to find some more gigs in France since we already had paid travel to and from France. He was a big zero, not the slightest bit interested, implying that no one would want to hear our music. So that's when I phoned Giorgio, I had his Paris number, and he said "Sure! come round and visit."

So we did and we told our story of Assad's indifference. He said at first he couldn't help us but after the wine began flowing he phoned Georges Leton and told him to come over. Georges and I were happy to see each other again! Giorgio asked if Georges couldn't fit in some gigs around that time, using Robert as the selling point, since Soft Machine were huge in France (alternative circuit). So he did, and we ended up working the same circuit as Gong and Magma with the MJCs mostly.

That all ended with the Centre Pompidou which sucked away all the regional budgets to give to Boulez etc. No money for the regions, no money to pay musicians and groups. Isn't it marvelous?

Everyone outside Paris had to finance everything themselves so of course they couldn't. I think of it (not my quote) as Socialism for the rich and Capitalism for the poor.

But by then Henry Cow was over and Giorgio had gone to New York and I never saw him again.

[Rick] How had your relationship with Virgin evolved to the point where they were "doing a terrible job getting us gigs"?

[Chris] In the beginning Virgin was trying to corner a market in which they could afford to compete; so it had to be small and rather specialized. The level of celebrity they could access – and which fitted the musical taste of their A&R man, Simon Draper (Richard knew nothing about music and cared less) – focused initially on the Soft Machine and their immediate circle - and then widened out. So the first signings were Gong (Daevid), Mike Oldfield, David Bedford and Lol Coxhill (all from Kevin Ayres’ The Whole World), Mike Patto (also via Kevin) – and they tried hard to get Robert Wyatt, who initially turned them down – but eventually signed up. Henry Cow came to Virgin on the recommendation of Daevid, Robert (Wyatt) and the journalist Ian MacDonald (whose brother was in a band with Robert). So far, so alternative. But then, almost immediately, Mike’s album, Tubular Bells, sold 7 million copies and Virgin began to reorient to follow the money. Accountants took over and the early signings were gradually abandoned. Henry Cow had always organised its own concerts, but the Virgin agency promised to do better for us; and initially it did - by putting us on tours with other Virgin artists: Faust, Captain Beefheart and then on a double bill, with Kevin Coyne. Otherwise they got us almost nothing. We knew there was interest on the mainland of Europe but, our LPs weren’t distributed there - the licensees wanted Tubular Bells and the hits, not bands like us. Virgin had their sights on the bigger game and couldn’t see the return in making further efforts with their jetsam. Quite soon they’d make a move to get us out of their hair altogether; that’s why we were so keen to get into France and regain control of our concert bookings.

[Rick] When you arrived at Giorgio’s house in Paris, was this your first time meeting him? Do you remember your first impressions?

[Chris] He was friendly, accommodating and in the end spared us a whole evening to sit and talk. Serious conversation. Giorgio seemed to be a serious man - I mean serious in the sense that, unlike Branson, for example, he really cared about music, art, culture... and was both eloquent and educated. In the end we talked so long, he put us up for the night.

[Rick] How did the other band members react to Gomelsky's involvement? Did they take him seriously?

[Chris] Only Maggie and I talked to him. Then he passed us on to Georges and Christine. After that Giorgio didn't manage us or have any regular dealings with the band. He'd known who we were though - at that first meeting he'd said how pleased he was with his mention on the cover of (the Henry Cow LP) Unrest - in a credit to O. Rasputin for the (Yardbirds’) song 'Got to Hurry’. But I can say categorically that Giorgio was a serious person. He helped us when there was nothing in it for him. Of course, like many on the musical fringe, he was also a bit of a chancer and moved around the pirate circuit with other important players of the time, like Jean Georgakarakos and Jean-Luc Young. I'd say he was a flawed idealist. He cared about the music.

[Rick] Maggie, I'm curious about your reaction to Magma’s MDK demo tape as sounding "evil".

[Maggie] Thought that it sounded evil? The sound system in the Manor control was typical of its time, huge JBLs slung from the ceiling to give maximum listening pleasure and the sound was loud. The record, which is what most people have heard, has one tenth of the power of the demo, therefore hard to understand the power of it. 'Evil' must be because of all the crummy Hammer horror films I had seen at that time used this sort of music to indicate Satanic rituals. I think that's why, just a cliché. I asked Giorgio if he knew where that demo ended up since the record was so lame, and he said "which demo?" Apparently there were many. I have the feeling that Francis Mose played on it, because Jannik was completely new at that time (although Christian and Isold, which has Jannik, came out in 1972) so I'm probably wrong. Mose was working with Gong at that time until they got......Howlett.

[Rick] Again Maggie, you have a unique take on that album, calling it "lame" compared to the demo you heard. Obviously Giorgio was the "producer" of both. Did you witness or talk to anyone who was working with Giorgio in the studio on this record? Did you ever work in the studio with him yourself?

[Maggie] Yes it was tame, it had no life. It hardly came into the room. I understand that it was because it was flown about to add parts in other places in the world. But I only listened to it once on record, so it's a first impression. But then I saw and heard it performed live many times at the many concerts I went to.

No, I never worked with Giorgio, I was not employed as a sound engineer at the Manor. I suppose sound engineering back then, especially for rock music, was still a male preserve. (But I did watch my friends engineering; Tom especially.)

[Rick] Giorgio was somewhat infamous for releasing demos against a band's wishes.

[Maggie] Yes, the saying was: "Giorgio has everyone's bad gig on tape." But he came to the Manor with the demo for the purposes of recording there so it must have been the official demo of the time. I'm really not sure, and I don't know if you can find anyone who can remember - Phil Newell perhaps - but I have a vague memory of Christian and Jannik being there at that time, smiling encouragingly since they didn't speak English. But I'm probably mixing it up with when they came later. I know that 'Leg End" (aka Legend) was recorded over the Magma outtakes, and that was May 1973.

[Rick] Chris, do you have any memory of hearing the MDK demos?

[Chris] No, I never heard those demos, but I can believe they were better than the LP. In the end Mekanik didn't turn out as the band wanted, largely for technical reasons. In fact Henry Cow had a small and inadvertent part to play in that, though we didn't know it at the time. We were booked in to record at the Manor immediately after Magma left and Virgin re-used the 2-inch multitrack they had recorded Christian and Janick on for our first LP - I'm pretty sure that was because the band or Giorgio didn't want to pay for the 2" masters, so Virgin saved money by recycling them. I didn't discover that until much later when I was listening through the multitracks and found a few minutes of bass and drums at the beginning of the reel. I know this caused Magma serious problems (as I later heard from Simon (Hayward) and Stella (Vander)), because the band went on to add more and more parts - and to make space for them they had to bounce the bass and drum mix down onto just a few tracks. When it came time to mix, they needed to rebalance and re-equalize the rhythm section, but they couldn't - and they had no access to the 2" master, which in fact no longer existed. So the mix on the album suffered. I have to say I still like it, but it wasn't what Vander wanted.

[Rick] From what Maggie said, it was the adding of more parts that diminished the power of the original demo that she heard.

[Chris] Yes it was the adding of more parts, a lot more parts. For technical reasons to do with the way frequencies interact bass and drums may be crystal clear alone but more murky and ill-defined when sunk into a sea of other sounds. When the tracks are separate and accessible you can psycho-acoustically correct this through equalization, amplification and panning, but if the bass and drums are mixed down already, you can’t do that.

[Rick] Gomelsky would move to NY and produce the live Zu Manifestival. Did you stay in touch with him much prior to this?

[Chris] Not really.

[Rick] How did you get involved with the Zu Fest?

[Chris] Initially through Gong - I was working with Daevid and Gilli (Smythe) at the time. I often filled in when the band was between drummers, or when Pierre (Moerlin) was otherwise engaged. We all flew over together from Spain. So I flew in with Daevid and Gilli and I’m sure that was paid for by Giorgio. We arrived maybe a week before the concert. And a small correction: the group listed as 'The Fred Frith Group' on the recordings was actually the Peter Blegvad Group, hurriedly got together by Peter and I at the last minute. We asked Fred - and Billy Swann from the Muffins (who I notice isn't mentioned on the recording) - to join us and perform a few of Peter's songs. Peter was living in NY at the time, but I don't think Giorgio knew who he was.

[Rick] I'd like to hear about your experiences at the Zu Fest ... meeting new musicians, working with the crew, preparing for the show, etc.

[Chris] It wasn't the whole of Gong that flew to New York - I think just Daevid, Gilli, and I; maybe Dider (Malherbe), but I don’t think so. We rehearsed the material in the basement with Bill Laswell - and possibly other members of the group that eventually became Material. I tried to refresh my memory about this online, but all the sources I found got the Zu Gong line-up wrong.

[Rick] Do you remember what the Zu Gong line-up was?

[Chris] I think: Daevid Allen, Gilli Smyth (the Spanish contingent); the New Yorkers were Bill Laswell (bass), George Bishop (sax), Michael Lawrence (guitar) and Michael Beinhorn (synth).

[Rick] Above you said you also played with the Peter Blegvad group. Any other groups that you can recall? Any spontaneous improv happen?

[Chris] Not that I remember, Peter and I just put the quartet together. That was spontaneous, but that was all I think.

[Rick] Do you remember any of the other groups that performed, or the "panel discussion"?

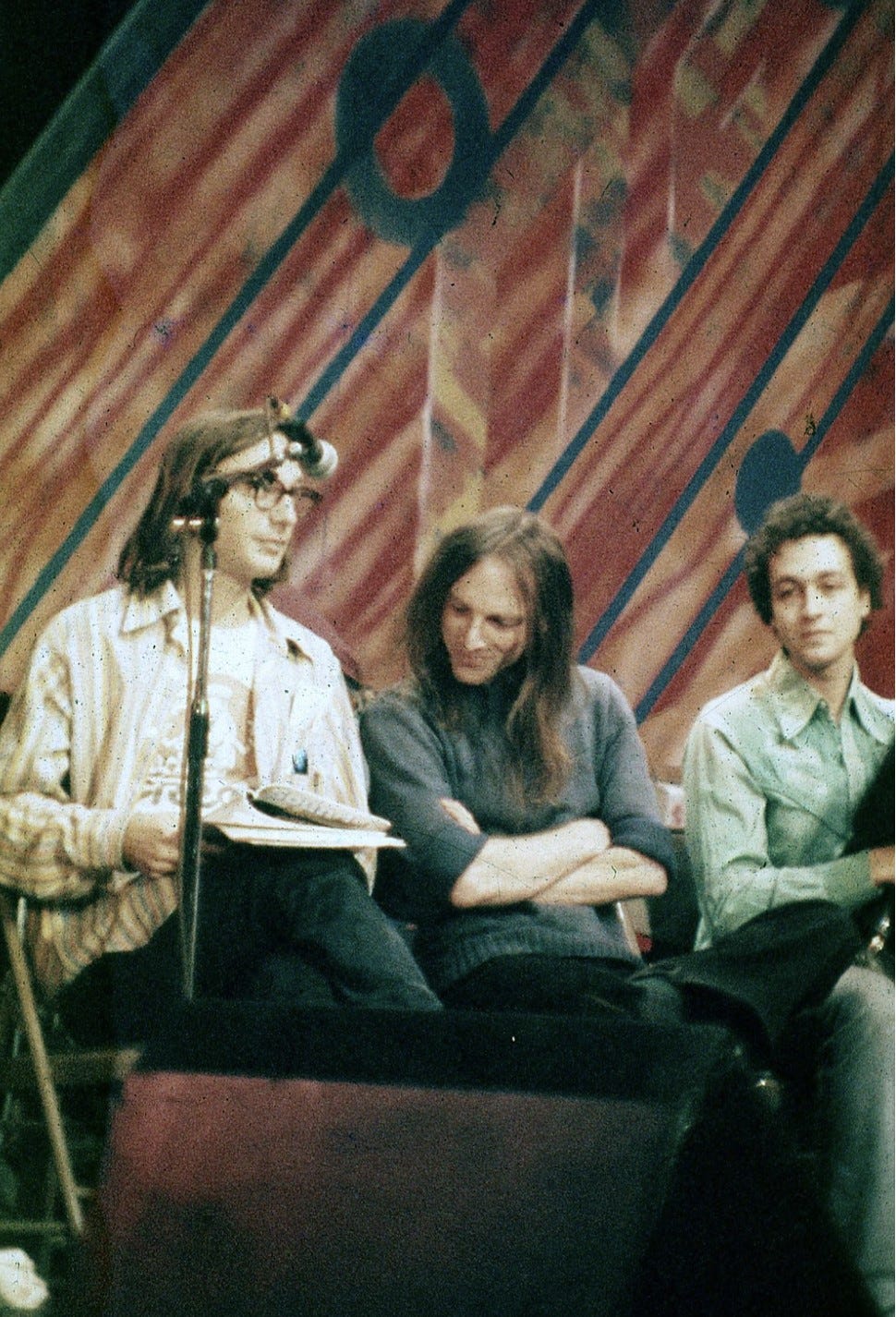

[Chris] This photo is from that panel discussion. It’s from the right period and it’s certainly NY (that’s Robert Christgau next to me) – and I think I remember that backdrop - but I don’t recall the substance of anything discussed. It was a day in the life I’m afraid.

Recordings from the Zu Fest including the panel discussion can be heard here:

[Rick] What impact do you think the Zu Fest had on the avant-garde music scene? Did it have much of an impact on you?

[Chris] The Zu Fest introduced a lot of what was happening in Europe to New York - and gave some of the fringe Americans a very visible platform; most important was the fact that it happened, that someone made it happen; it caused ripples and I'm sure the reverberations were of significance.

- On me? Not so much. I knew many of the people already and I was familiar with this European way of doing things. Interesting to work with Bill (Laswell) though. Nice guy, excellent bass-player. The whole rehearsal period was fun and trouble free. To the extent that I recall at all, I don’t remember any problems.

[Rick] Did you ever work with, or stay in touch with, Gomelsky again?

[Chris] I never worked with him, but we'd meet from time to time when I was in New York. I thought, like you, that his was a life that should be got down in detail while he was around to tell it, but I never got around to doing anything about it. Which I regret.

[Rick] Do you have any thoughts on Giorgio Gomelsky's influence on music and culture?

[Chris] It was immense - but in a subtle way. Apart from his unerring nose for what was original and great, he was a doer. He made things happen. And he thought creatively: the way McLaughlin’s Extrapolation was produced, for instance - like a rock record - was a first.

Where he landed, things happened: so, in the UK in the early to mid '60s his clubs played a vital part in the growth of the grass-roots R&B bands, which slowly morphed into the more radically innovative psychedelic bands of the later '60s and unarguably changed the way rock was thought about, and what musicians found the confidence to do. Then, in France, almost immediately he identified the best and most interesting bands and set about creating the first alternative gig circuit in the country, from scratch - en route encouraging civilian fans to set up their own associations and promote gigs themselves. This permanently changed the music scene in France.

Then he set out for the USA, I guess hoping to do the same again. But it was already too late. But it wasn't Giorgio who changed, it was the times - for once the words Billy Wilder put into the mouth of Gloria Swanson were true: “I'm still big, it's the pictures that got small.” That brief window where there were Rolling Stones and Soft Machines and John McLaughlins and Magmas to discover - and, more importantly, a substantial audience hungry for something new and better - was over. Pop went back to the industry and into the doldrums. Mainstream innovation petered out and musical experimentation coming from the grassroots no longer found its way into the mass arena. Even if Giorgio had moved again, I doubt things would have gone differently. The rules had changed. All you could do then was hold on and maintain standards. And do what you could when you could.

[Rick] I would like to ask you a couple of questions in closing. First is about the book on Henry Cow, The World Is a Problem by Benjamin Piekut. What did you think of it?

[Chris] Here’s what I wrote in ReR catalogue at the time: This is an academically motivated, but for the most part straightforwardly told story that tries painstakingly to piece together what was going on in Henry Cow in respect both of its individual internal relationships, and in the way these intersected with the band’s collective negotiations across the interlocking spheres of the world at large (i.e. commercial, political, sexual, theoretical, practical &c.) It tracks the band chronologically from its inception to its orderly close, employing a wealth of testimony, interviews, contemporary documentation and private records. All the surviving members of the band co-operated, giving Ben whatever materials they were willing to make public - some more than others, which is why, inevitably, the perspectives of the more generous record-keepers are more prominent. Ben also interviewed everyone he could find who had ever worked or travelled or had significant contact with the band, listened to every bootleg and read every article and interview. The research is thorough. For the rest, Ben has had to interpret, edit and, occasionally, take sides as he tries to fit what he has into a sociological narrative. No one in the band will agree fully with his analysis, but neither would they agree fully with one another’s; subjectivities are profoundly complex. For most of the book, Henry Cow’s actions and negotiations with the world are well served - it’s a thorough and detailed history. But when it comes to their negotiations with one another the narrative necessarily takes the form of an attempt by the future, guided by its own biases and interests, to unearth things that were already hidden when they were current - by which I mean motives, hopes, ambitions, insecurities and the ties that bind and undermine. This aspect of the book is uneven because the testimonies are uneven. And, at a point, Ben wanted to wrap it up so he didn’t go back to interviewees to clarify or confront one with another’s account. Interpretations just float, there’s no editorial attempt to get to the bone. That clarified, it’s a cornucopia of invaluable information – just sometimes best to read between the lines.

[Rick] Maggie?

[Maggie] Here’s my 10¢ worth on Ben Piekut whom I rather unkindly called an "overqualified journalist". I was with HC for 4 years as their sound engineer. He asked me six questions, of which five were related to Georgie Born. I hesitate to call this a bias...but he was her pupil...

Also he decided not to find or interview Joel Schwarz, a long time sound engineer (who would have known Giorgio well) but did dig up far more marginal contacts (at least two of whom, both female, refused to co-operate after speaking to him).

After gathering his question bag together he then asked us to verify that we had actually said these things - these quotes: (I ..Maggie Thomas...hereby affirm that I said such and such a thing).

Lastly he said that this or that quote was to be included in his text and stated straight off that he would not reveal the context in which they appeared - "bear with me" he said.

I insisted on knowing the context, and when I found that he had applied one quote as my judgement on a meeting at which I wasn't even present nor had said anything about, I told him not to use my quotes since he seemed neither to be an accurate chronicler nor to care very much about the music itself. We parted on bad terms!

[Rick] And finally, Chris, what are you up to now?

[Chris] Right now concerts are beginning to get back to density after the covid hiatus, so I’m performing – in a variety of different projects and recording now and then. I’m still working on the research/educational podcast series I’m making for the museum of modern art in Barcelona, now at episode 72. And I recently published a new book of essays and still intermittently engage with academic work.

[Rick] There have been some Henry Now gigs fairly recently. How has it been revisiting that music and musicians and fans?

[Chris] Well first, we didn’t revisit the music. And neither did we decide to reform. As you know all of us have played together in many different constellations since the breakup of Henry Cow, often in improvising contexts. Henry Now came about because Fred and I did a gig in Paris and invited John to join (he lives there); an Italian promoter saw the concert and invited us to Italy, proposing we also invite Tim. Just to improvise, not to play any of the old repertoire. Then he, the promoter, suggested the name Henry Now. Full disclosure: I was against the name, for many reasons, but everyone else agreed, so… Playing together was great - as always, and the public were happy, in spite of the absence of old repertoire. Henry Now isn’t Henry Cow and I think they got that.

But, we did, once, reconvene the group properly, to play (some of) the old repertoire, for our bassoonist and saxophonist, Lindsay Cooper at a memorial concert we gave for her at the Barbican in London. To that, people did show up from all around the world; it was a highly charged evening. Never to be repeated.

Chris Cutler: www.ccutler.co.uk

Probes podcast series for Radio Web MACBA

The Museum of Modern Art, Barcelona: https://rwm.macba.cat/en/buscador/radio/serie/probes-9468?sort=date&order=asc

Further info:

A Celebration of Lindsay Cooper review – avant garde pioneer remembered

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/nov/23/celebration-of-lindsay-cooper-barbican-live-review

Henry Now

https://rachot.cz/henry-now-chris-cutler-fred-frith-tim-hodgkinson-john-greaves/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOVbnHI92Es

Magma's Mekanïk Destruktïẁ Kommandöh was partly recorded at the (Virgin Records') Manor Studios but not released by Virgin Records. A&M released it.

What an excellent interview, Rick, congratulations. I guess you will never cease to amaze me. You are like an archaeologist digging and finding these buried treasures regarding this particular part of Giorgio's life.